Version Control for Scientists

Version control systems allow people to work iteratively on content, code, and materials with the confidence that their work won’t be lost and that earlier work can be easily revisited and reproduced. These systems also allow advanced collaboration: with distributed teams working on parts of larger systems at the same time and having the confidence that they can “merge” all the changes back together in the future.

The most advanced and flexible version control systems come from software engineering and decades of development there have resulted in mature, distributed version control systems. Git (https://

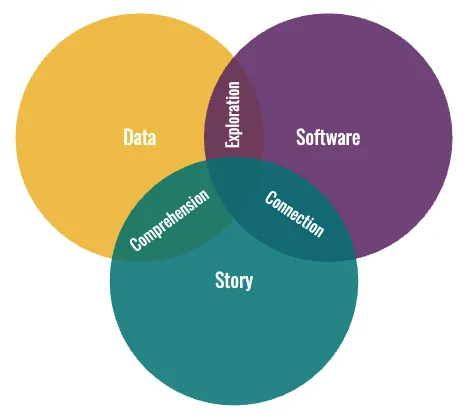

These version control systems were designed for software development workflows. Git was not designed for scientific workflows around exploration, experimentation, writing, teaching, data, attribution, and software*.*

Scientific exploration and experimentation is different from software development.

Writing is different than programming.

At Curvenote we are exploring version control and collaboration workflows that are designed specifically for the research workflow. We are thinking about what a “unit of content” is for these workflows, how that content is updated, modified and reused in other documents and presentations.

The push for git¶

Git is powerful and excellent at supporting software development workflows. As data-based research and software becomes more prevalent across all scientific fields there is mounting pressure for scientists to adopt git as a version control solution in their work. There are many challenges that scientists face when working with git:

- Git is complicated with a steep learning curve: requiring a scientist to learn many abstract concepts often far from their primary field of work.

- Git tracks and represents changes to text files on a line-by-line basis. This works well for code stored as text but doesn’t for many other types of data and content.

- Git doesn’t easily support mixing binary data, structured objects, and content — meaning document structures like Jupyter notebooks or Word files are not well supported.

- The unit of collaboration is the “repository”, which means reuse or collaboration at other levels (e.g. a file or a part of a file) is not well supported, especially across different repositories or teams.

Successful collaboration with git often requires many steps including pulling local changes, branches, conflict resolution, and “pull requests”. While suitable for software development workflows, this is often cumbersome when working with binary data, using git for writing, making many small fast changes, sharing and reusing components of a repository, or exploring ideas that may never make it into a branch that can be shared.

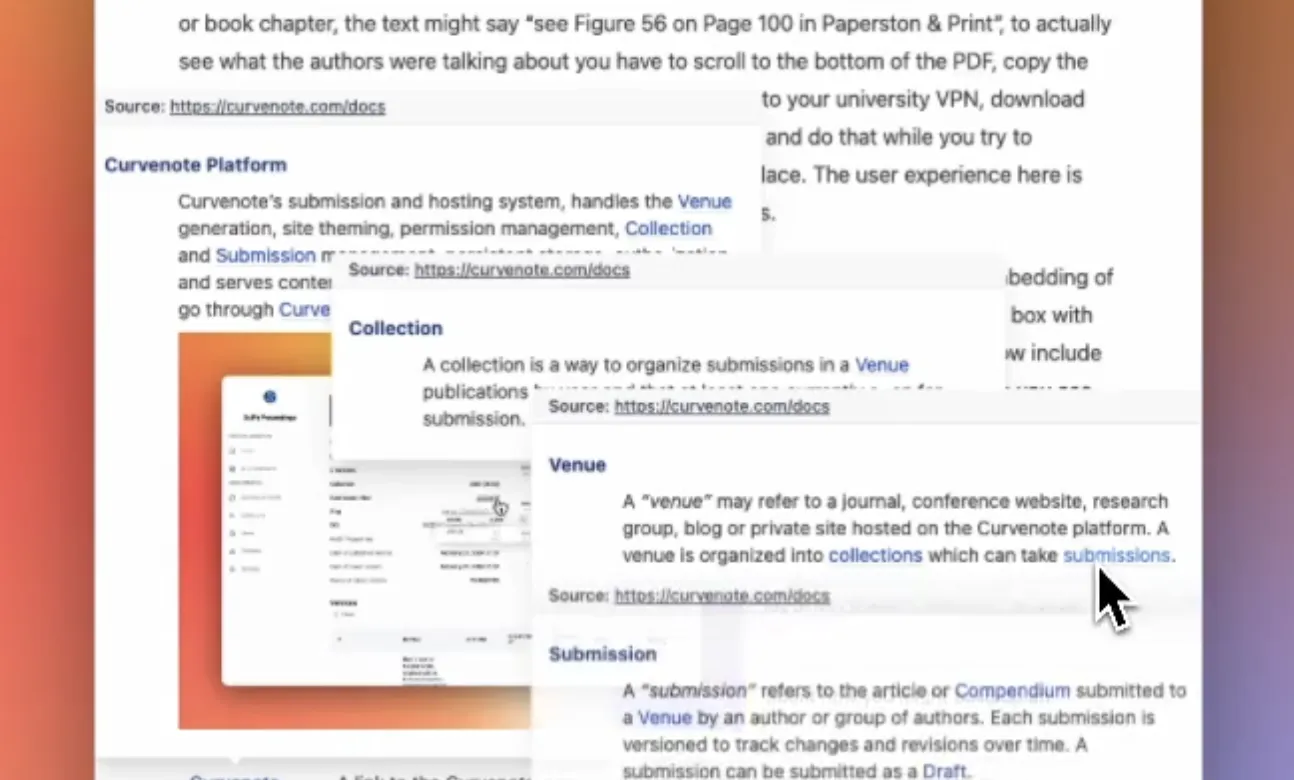

In the rest of this post, we are going to go through some of the basic concepts we have introduced in Curvenote’s version control system in our online, collaborative editor and our Jupyter Chrome Extension.

Version control for scientists humans¶

Blocks¶

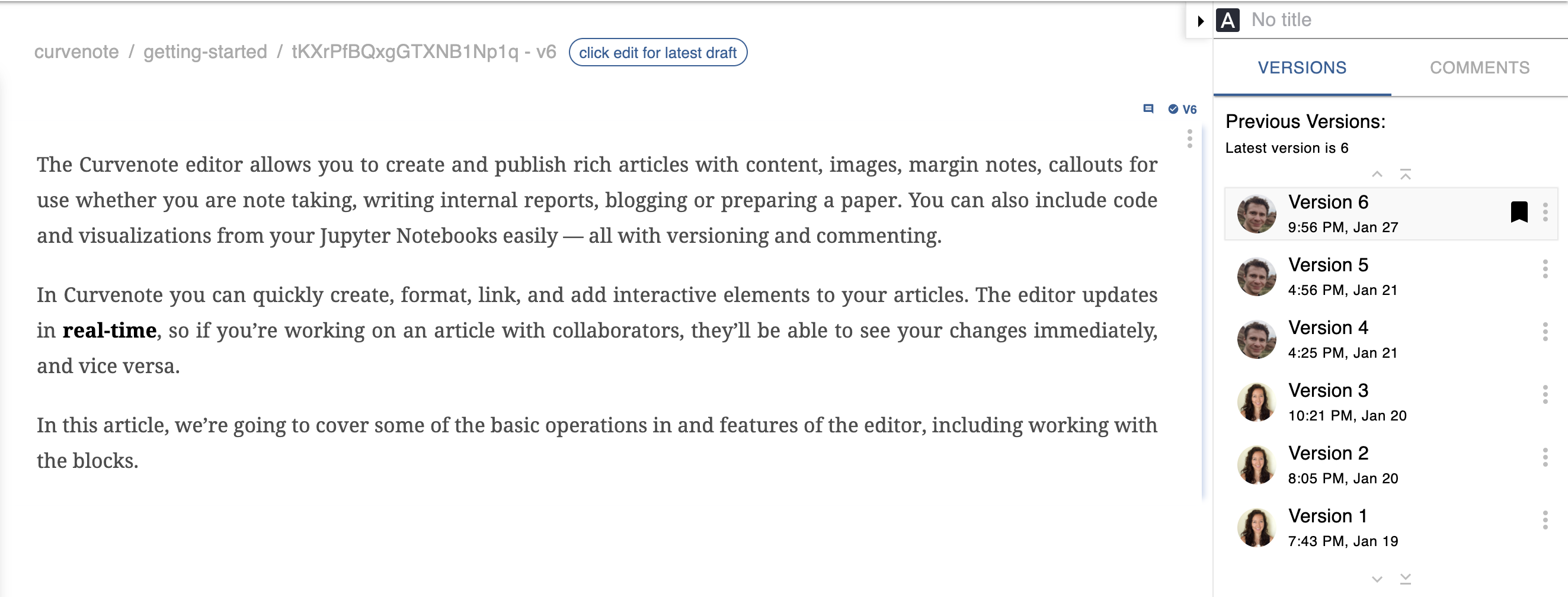

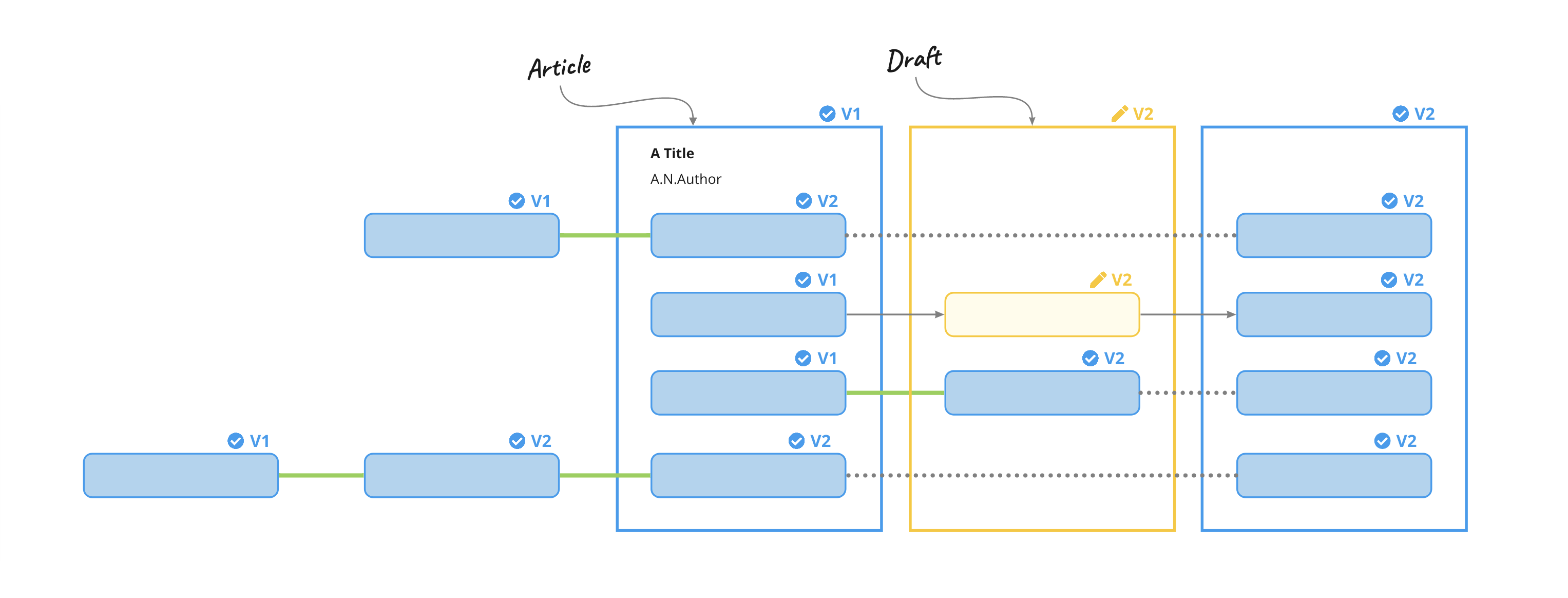

Curvenote content is organized in blocks, whether that be a block of text, code, an image, or a Jupyter notebook output. For the moment, we’ll think of blocks of text as you would create in our online editor. If you go to any existing Curvenote article and select a block you’ll be able to see the version history for that block in its entirety. Just like the block shown below.

Each version of this block is a complete snapshot of the content at the point in time the content was saved. Versions are saved as whole blocks (rather than changesets), are immutable, and can be stepped back to at any time.

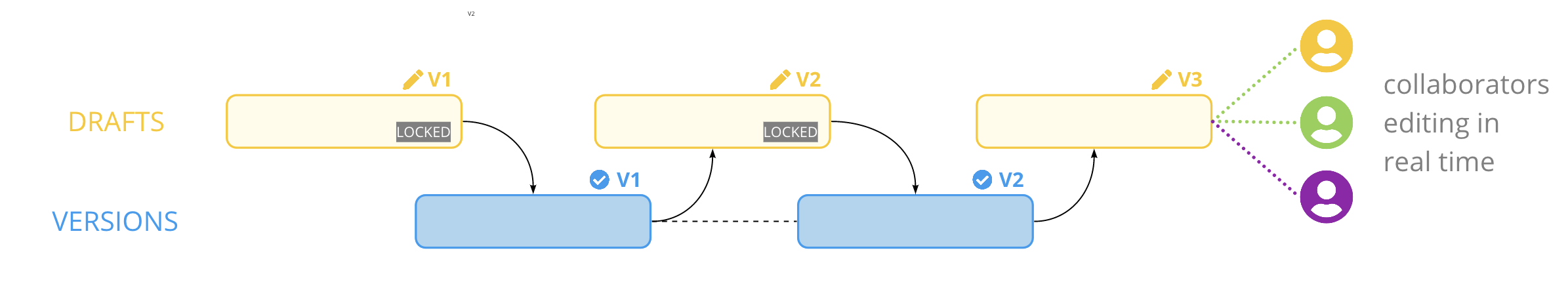

That’s clear enough, but what happens when we are editing a block and have yet to save a new version? This is where Drafts come in.

Drafts¶

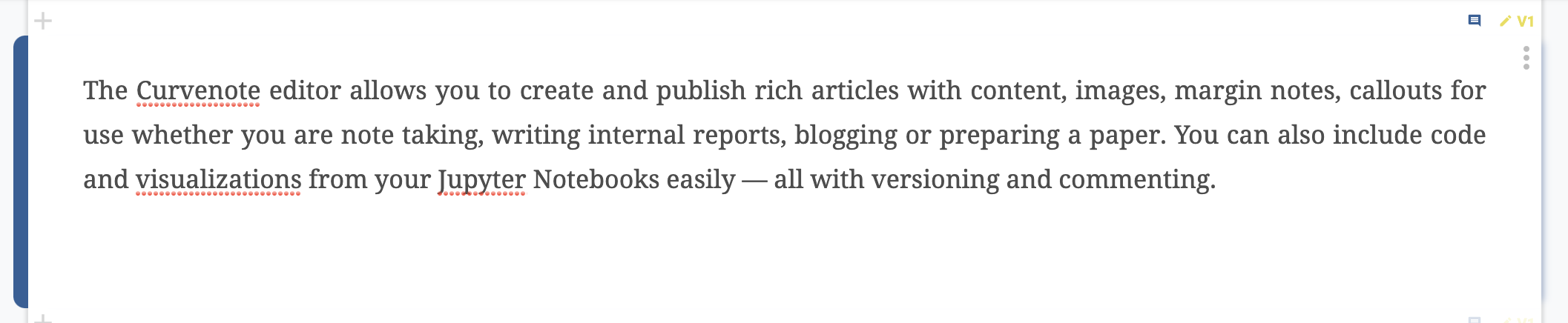

Let’s take a step back and think about a block the has just been created in the editor first time: v1. That will look something like this:

Figure 2:The initial draft of a single block in the Curvenote editor. Notice the yellow (which means draft) V1 badge at the top right.

A new block has been created along with an initial draft. Drafts are updated in real-time and are fully collaborative. That is, multiple users can be editing a draft at the same time and all of their changes are captured and recorded as one big changeset. Drafts are persistent and allow changes to be made over multiple browser sessions, from multiple collaborators.

As we iterate on our writing, we create drafts and close them each time that we save and all the changes are flattened back into a consistent snapshot and stored in the next version. merging and locking of drafts is some internal terminology that you may see crop up in places. New drafts are always created on top of the latest block.

All of the individual blocks in Curvenote behave in this way and practically all content you see in Curvenote are represented by blocks; text, images, citations as well as Jupyter code and output blocks. Even Articles and Notebooks themselves are blocks.

Articles¶

Yes, you read that right! Articles themselves are blocks and subject to the versioning flow as shown above.

Just to be clear there are two document types:

Articles that you create directly in Curvenote online and Notebooks that you create either by uploading an ipynb file or saving from Jupyter via the Chrome Extension.

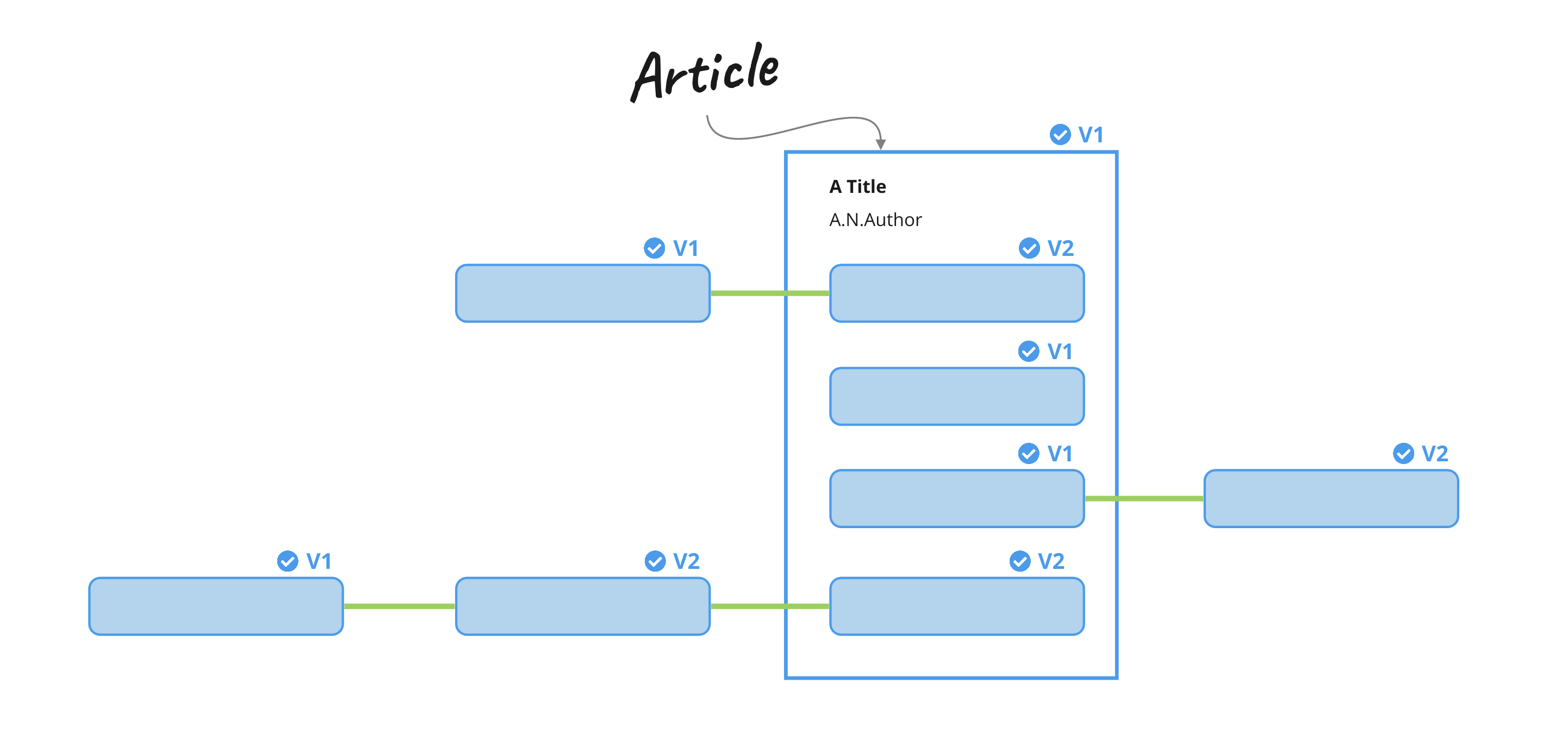

Articles are containers that group together a collection of other blocks (children) along with additional metadata. We use Articles to create content based on writing, import content and reference various other blocks.

The children blocks of an article can evolve independently, potentially also changing elsewhere, and are likely to be various different versions, whilst the article itself has its own version history. Articles are like manifests detailing the current versions of their children blocks.

This base data structure makes for a very powerful and flexible way to represent and track documents as we work on them supporting things like selective editing, insertion, removal, reverting, and updating of blocks as well as being able to share and reuse blocks between multiple articles (and notebooks!) and easily keep them up to date.

As we work collaboratively on Articles, they also have drafts of their own which track child blocks, versions, and drafts as we collaboratively edit. This may seem a little complex but it fits well with how we write in practice: thinking about a paragraph, figure, or an equation as a unit of content.

Notebooks¶

In the Curvenote system Notebooks are also containers like an Article but with some key differences.

This stems from the fact that Notebooks are primarily edited and worked on in Juypter and saved to Curvenote in one action via a chrome extension. Also because of additional rules Jupyter enforces for computational reproducibility, mainly that output cells are always children of code cells.

When editing a notebook in Curvenote online, for example, to update its metadata and add a thumbnail, change its named URL or add a binder link, or to add or edit markdown blocks — things work pretty much the same as an Article. Whereas code and output cells cannot be edited online.

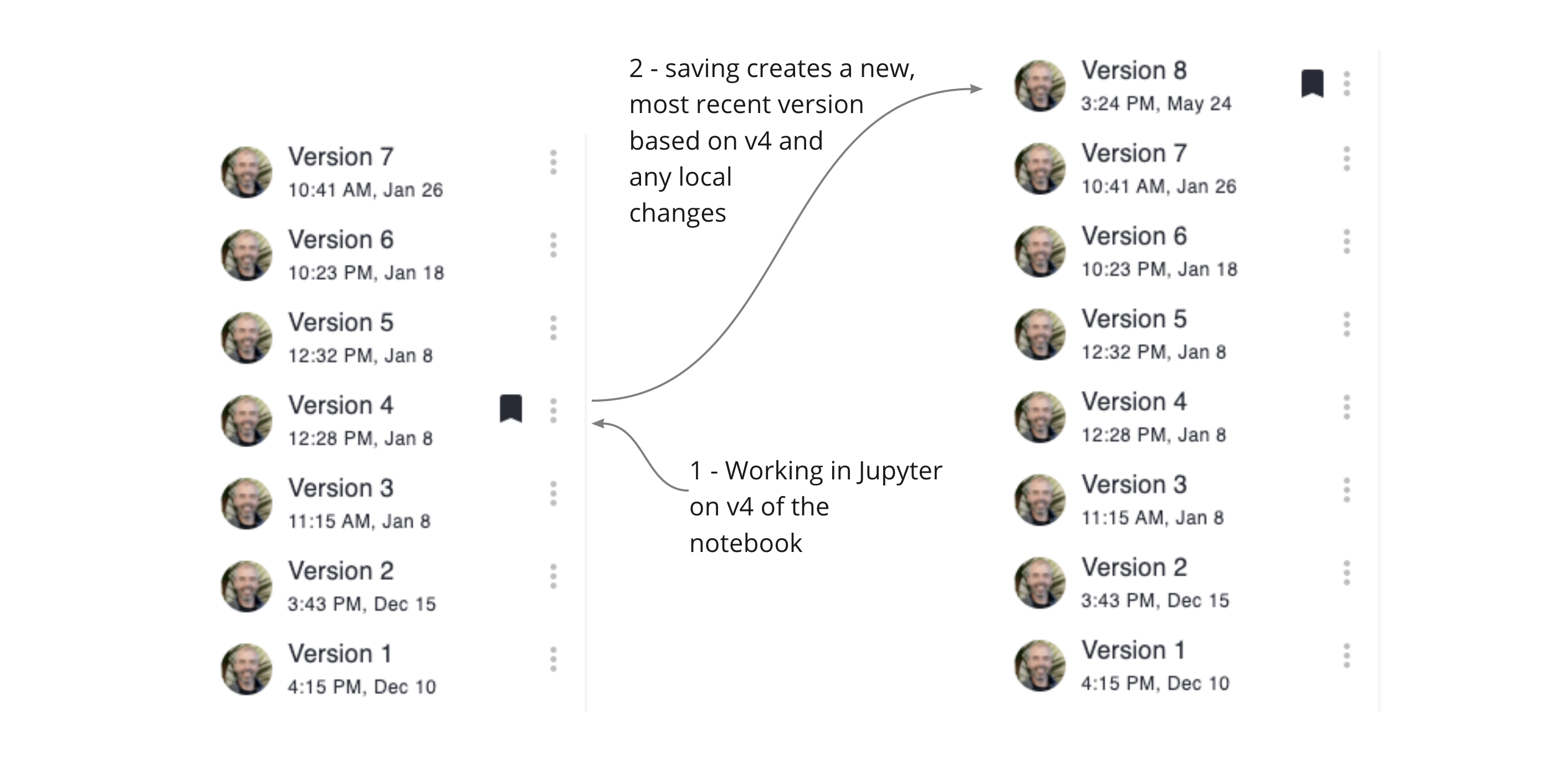

When working in Jupyter however, using the Curvenote Chrome Extension you of course have the. ability to fully change and execute the notebook as normal — but there are two important behavioural differences in how versioning works:

- There is no draft - when we save we immediately save a new version of the notebook and blocks.

- It is possible to revert to an earlier version of a notebook, make changes and save a new version — effectively “leap-frogging” changes into a new and most recent version. (This is a little like a rebase in git).

What’s next¶

Curvenote’s version control system is evolving. In our quest to make accessible and easy-to-use version control for scientists and researchers, we have established versioning around blocks and maintaining links in a graph of connections between blocks, containers, and versions whilst you write, code, compute, share, reuse and create new ideas.

A lot of the work and learning ahead of us is around how to provide the right mental models, appropriate terminology, and user interfaces.