Reusing & Remixing Scientific Content

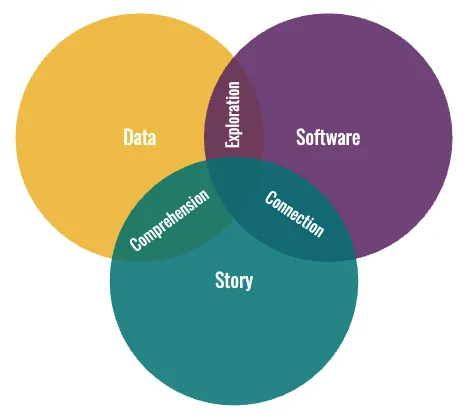

As a researcher, you explore ideas and communicate them in many different ways: at conferences, in papers, in blogs, in documentation, in emails and messages, and in notebooks. As a researcher using computation, you are exploring ideas in Jupyter Notebooks. However, throughout this process of communicating, your work evolves and then necessarily migrates out of this computational medium: results as images and screenshots, text is copied into other documents never to return.

If you are in charge of keeping these documents up to date (e.g. for presentations, reports, courses, tutorials, documentation, etc.) the collaboration overhead is difficult and excludes those without time or knowledge to engage in a complicated process. Our current tools are also pretty clunky at facilitating collaboration between technical and non-technical stakeholders, for example, your boss, your students, or your busy colleagues.

Open Source¶

In the open-source programming world, there are lots of tools, processes, and social support to improve and iterate a package “in-place”. Imagine if instead of version control, issue management, and continuous integration we were sending disconnected copies of a package to our users. The overhead to improve that package, that idea, would be enormous. The ability to import other people’s work with a clear license of how to use it enables a social contract of maintenance, improvements, and related extensions. In software, without the technical infrastructure, social and legal contracts, we would perpetually be starting our scripts from scratch.

Writing¶

Unfortunately, this is exactly where we find ourselves in writing documents and communicating our presentations. Linking content, such as a figure or variable, to its provenance or computational workflow is generally impossible. Almost no technical infrastructure exists to reuse content beyond a single document. If you have a relevant figure, equation, or paragraph that has the potential for reuse it is commonly duplicated through copy/paste. Unlike the open-source programming world, where we can “import” an idea, there is no license associated with that work and there is no chain of attribution - this has direct consequences:

- fragile provenance and reproducibility,

- potential copyright infringement, and

- perceived or outright plagiarism.

In writing and communicating, we are forced to perpetually start from scratch.

As such, individuals either ignore those problems (not citing images, or copied text) or in more formal settings spend effort rewording paragraphs and redrafting pictures. Both of these outcomes are rather unfortunate: previous ideas are not credited and/or there is wasted effort to remold existing ideas. If you think that is not wasted effort, imagine having to “re-word” an array library/package before you use or publish your idea that builds upon it!! Although it might be a good learning exercise, often what you are working on needs to build upon previous work: in scientific communication, we are essentially forced to perpetually start from scratch.

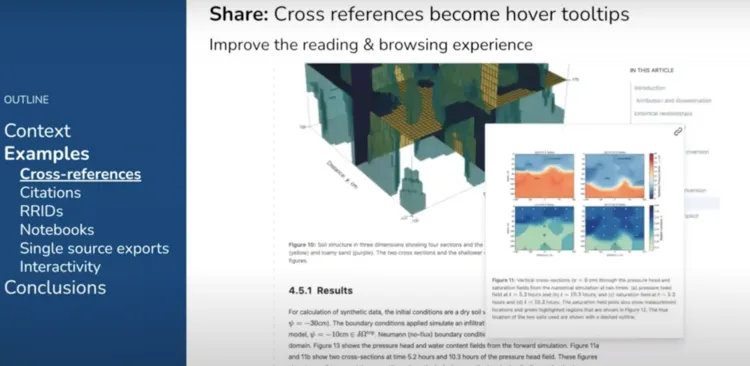

There is a secondary consequence as well: these ideas (paragraphs, images, equations, tables, etc.) cannot be improved. “Users” of that idea can not subscribe to updates or new versions. There is no ability with these technical and social barriers in place to “iterate in-place” while providing a link to your future work.

Reuse and Remix¶

This small reuse is pervasive, even when you are using the best modern version control systems and the best real-time collaborative document environments. There is untracked duplication between projects, notebooks, and documents that is not allowing us to link, track, and collaboratively improve those ideas over time.

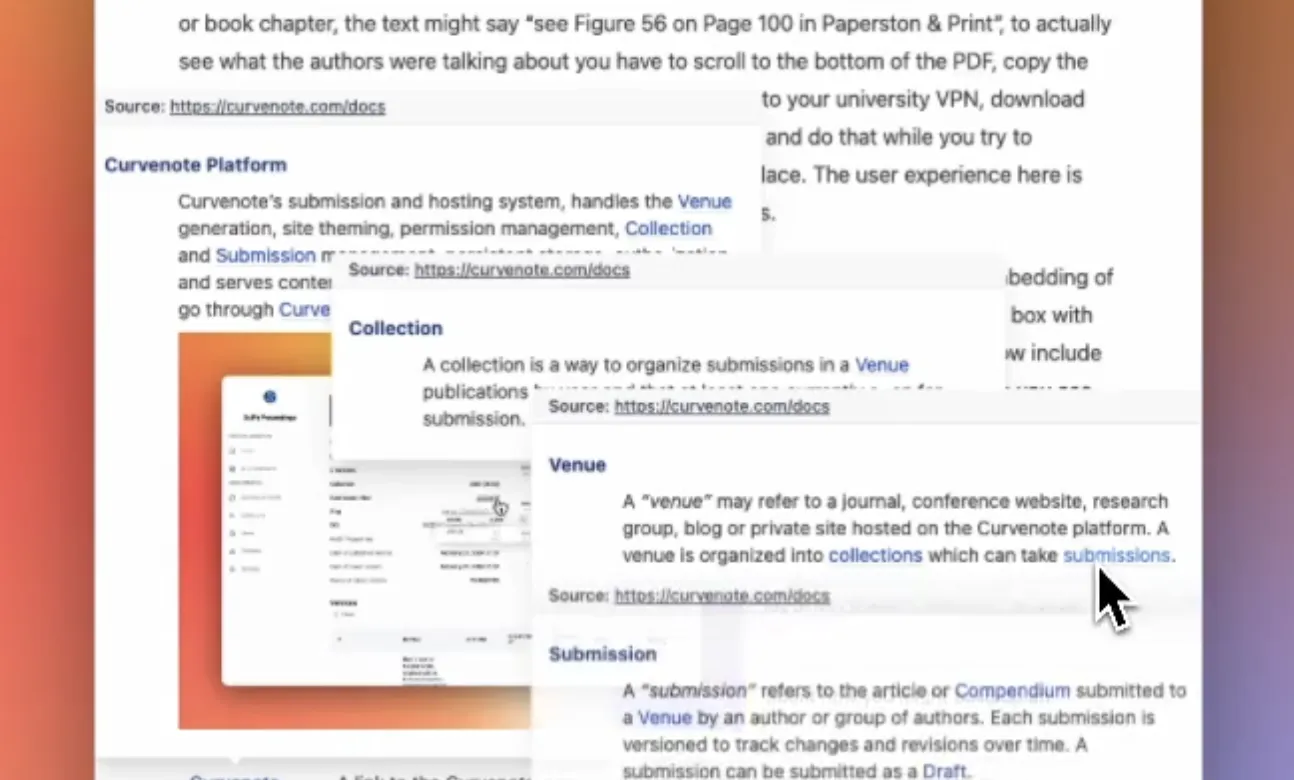

Our goal with Curvenote is to introduce tools that can lower the barrier to linking, tracking, and enable the possibility to collaboratively act on improvements.